Newspaper headlines moralising about binge-drinking ‘ladette’ culture and alcohol-fuelled crime are hardly a recent phenomenon. I was reminded recently of my own half-forgotten research about Victorian drunkenness by Nell Darby’s excellent blog post concerning the newspaper reporting of the 400 arrests of Annie Parker in mid nineteenth-century London. This empathetic account of a ‘notorious’ woman whose alcoholism earned her censure, pity, and not a little admiration was a familiar story in the later Victorian and Edwardian period as well. Craig Stafford’s work in nineteenth-century Salford and Rochdale also reflects this fascination and revulsion with these highly visible and noisy women with headlines such as ‘The Worst Woman in Rochdale’.

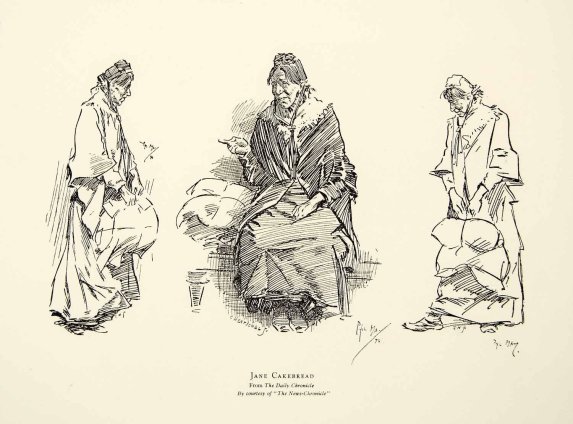

Record-breaking arrests seem to be the favourite headlines for newspapers, and probably the widest known ‘habitual drunkard’ was Jane Cakebread whose nearly 300 arrests had generated extensive column inches of the ‘Jane Cakebread Again’ sort. She was discussed in the British Medical Journal, and her ‘fame’ spread to the US via a 1897 piece in the North American Review.

Illustration by Phil May

In 1904 the BMJ printed a report by Dr. Robert Jones, of Claybury Asylum, where Jane had apparently ‘found rest for three years till her death’. However, a missionary visitor had reported to Lloyds Weekly newspaper that she preferred life in Holloway Gaol where they ‘understood her so well’. Jane had been the subject of a concerted newspaper discussion as to what could be done with these women. In 1895 Lady Henry Somerset had established a ‘Industrial Farm Colony for Inebriate Women and Babies Haven’ near Reigate in Surrey. Although Jane turned down a personal invitation to come to the colony, she spoke with pleasure about the dress Lady Henry had given her.

The Habitual Drunkards Act of 1879 had enabled residential treatment as an alternative to prison for habitual drunkards, although its cost was prohibitive for many poor and working-class women. The 1898 Inebriates Act empowered local councils to establish and administer certified inebriate reformatories which were paid for by central government, local authorities and charitable donations. The 1902 Licensing Act gave breweries the power to ban habitual drunkards from their pubs, and subsequent mug-shots and stories of female inebriates is discussed brilliantly by Lucy Williams’ Wayward Women blog.

From the Illustrated Police News 1886

Unlike the rescue and reform of ‘fallen women’ the institutionalisation of inebriate women was not as popular a cause and lasted only from the end of the nineteenth century to the First World War. It was an enterprise riven with failure as many women were arrested for alcohol related offences very soon after their release from a reformatory. In 1904 the Weekly Mail reported that Swansea’s Margaret Rogers (aka ‘Mad Maggie’) was back in court four days after she returned from a two year stay in the Bristol reformatory. However, like homes for ‘fallen women’, only a very small percentage of ‘inebriate’ women actually attended any institution, and were lionised, demonised and the impact of alcohol on their lives, their families and civil society was fretted about in newspapers regularly.

In Wales, newspapers seemed to compete for the ‘worst’ offender. Both Emma Retallick of Pontypridd and Ellen Sweeney of Swansea were referred to in the press as the ‘Welsh Jane Cakebread’. In turn, Dorcas Carr was portrayed as being ‘still young enough’ to rival Ellen Sweeney. Mary Norman was also known around Swansea (and in the newspapers) as Lady Tichborne. In 1898 it was reported that she was giving up her inebriate lifestyle and moving to Ilfracombe to live with her married daughter. Her return was reported by the South Wales Daily Post in a tone that might embarrass some of the more sensationalist press today, and portrayed her as a standing joke.

Lady Tichborne on Tour

Poor old ‘Lady Tichborne!’ Her stay at Ilfracombe must have been of a brief duration. A day or two ago she was seen standing against the wall of a butcher’s shop in Cardiff in the old hilarious style. Her face was besmeared with dirt, and appeared as though it had not been washed since her departure from Swansea.

Mary was around 78 at this time, and she died in Swansea workhouse nine years later at the age of 87.

Many of these Swansea women spent time in the workhouse and prison. The registers for Swansea Gaol show many women in and out of prison on an almost monthly basis charged with drunkenness, theft, immoral or riotous conduct. The workhouse registers tell a similar story, and like Mary Norman, some died there including Dorcas Carr and Ellen Sweeney.

Ellen Sweeney c 1896

Ellen Sweeney’s stays in the workhouse were often marked by her resistance to authority. In 1885 a poor law guardian reported that ‘inmates generally doing well with the exception of Ellen Sweeney whose conduct to all, officers and inmates, is unbearable’, and a week later that her conduct was ‘worse than ordinary’.

In both 1879 and 1889 the workhouse medical officer had tried but failed to establish that Ellen was insane so she could be transferred to a lunatic asylum. Whether their motive was to help her or to rid themselves of a nuisance is difficult to determine. She was undoubtedly a serial offender; in 1893 she was imprisoned for drunkenness, it was her 257th conviction and she had been out of gaol for just one day. A year later she was convicted for the 269th time.

The manner in which Swansea newspaper The Cambrian reported her death in 1896 demonstrates the complicated and contrary attitudes shown to Ellen, who the paper called ‘one of the greatest female inebriates in the Kingdom’. She was lionised by her capacity for inebriation, pitied for her ‘wasted’ life, and sanctified for her periods of sobriety in prison and workhouse which were apparently marked by devout prayer, scrupulous cleanliness, intelligence, and her nursing skills.

In a later piece The Cambrian blamed society rather than Ellen and stated that inebriates should not spend their lives between the gaol and the workhouse as they were not responsible for their actions and forecast, somewhat optimistically, that ‘the treatment meted out to her will not be tolerated 15 years hence’.

The newspaper reports have all been accessed via the wonderful and freely available National Library of Wales’ Welsh Newspapers Online

Further reading:

Peter Carpenter, ‘Missionaries with the hopeless? Inebriety, mental deficiency and the Burdens’, British Journal of Learning Disability, 28 (2000), 60-64.

G. Hunt, J. Mellor and J. Turner, ‘Wretched, Hatless and Miserably Clad: Women and the Inebriate Reformatories from 1900-1913’, The British Journal of Sociology, 40:2 (1989), 244-270.

Deborah James, ‘”Drunk and riotous in Pontypridd”: women, the police courts and the press in South Wales coalfield society, 1899-1914’, Llafur, 8:3 (2002), 5-12.

Craig Stafford, ‘Policing Salford’s Drunken Women’, talk to Salford Local History Society, July 2014, and ‘”The Worst Woman in Rochdale”, Mary Kelly and Female Drinking Networks in Mid-Victorian Rochdale’, Social History Society Conference, March 2015.

I have come across many very similar reports in Limerick in the 19th century. A lot of prostitution reported then too.